How tree view is done

In this section we will talk about how we implemented the tree view that can be seen in the side bar of hte explorer level

Data files

To implement tree view we need to have data that will be displayed there for this purpose 2 new classes were created. Each of those classes is inhering UObject so that we can later interpret and visualize these data.

CPP_TreeViewEntry

This is representing the roots of the tree. This is data that the class contains

FString FolderName - name of the folder that will be displayed

bool IsChild - is the folder child of another folder ?

int Depth - depth inside the tree, this will determine the padding of the folder

TArray<UCPP_TreeViewEntryChild*> Children - children of the folder componet that are visible in the scene and user can interact with

TArray<UCPP_TreeViewEntry*> SubFolders - other subfolders (not implemented and you can try to implement sub folders )

In addtion methods that are used to populate this class can be found as well. The methods are self explanatory and documented in code so i will not be explaineing them here.

We have used Builder pattern to aid us with readability since each creational method like SetActor or SetName returns reference to itself meaning we can chain call those functions like following

builder->SetName("name")->SetActor(actor)->SetComponent(component)->Create()

CPP_TreeViewChildEntry

Since we have two distinct visual components that display different information to the user, we needed to create a separate data class purely for the child components of the tree view.

This class bridges the gap between the user interface and world interaction by referencing the actual components in the scene.

The class contains the following properties:

UCPP_TreeViewEntry* Parent: The parent of this child entry.AActor* BodyPart: A general reference to the body part. This is a pointer to the Blueprint that holds the skeletal mesh for rendering and the static mesh for the picker. For more details, see the Adding New Parts to the Model section.UMeshComponent* BodyPartComponent: The mesh component it references. This could be either a skeletal or a static mesh component. We've chosen to allow you to pick either type, in case you want to add a picker mesh later.FString Name: The name of the component.int Depth: The depth value, used to calculate the padding of the children in the tree view.

This class also contains helper functions that are self-explanatory and return a reference to the class itself for method chaining.

These classes are primarily used for holding the data and for the creation of the tree view itself.

Tree View Widget

This widget lacks comprehensive documentation, but it shows great potential for displaying deeply nested data structures. We have only scratched the surface of what this widget is capable of, and we recommend exploring it further if you want to leverage its full potential.

The tree view widget is represented in C++ by the CPP_TreeView class, which inherits from the UUserWidget class. It contains a pointer to the TreeViewComponent, which must be bound to work properly.

In this class, we do the following: - Populate the data structure described above. - Push the populated data structure to the tree view.

Simple Example

Let’s suppose you want to add muscles. We'll assume you’ve already followed the steps in the Adding New Parts to the Model chapter. To add a new entry to the tree, you need to go to the NativePreconstruct function and use the provided helper function to push the new entry to the array of tree entries.

TreeViewEntries.Push(CreateTreeViewEntry("Muscles", FName("Muscles")));

The CreateTreeViewEntry function accepts two main parameters:

- The name of the folder to be displayed in the tree view.

- The tag associated with the Blueprint (or Actor) that holds: Skeletal mesh as the merged body part. Static meshes as its children (picker meshes).

This function works by retrieving all actors that match the provided tag. It then iterates over their child components and creates a CPP_TreeViewEntryChild for each SkeletalMeshComponent associated with the retrieved Blueprint (or Actor).

This process highlights one of the main reasons it's crucial to follow the standards we've established. If you decide to change these standards, you'll need to update the relevant classes accordingly. Otherwise, the tree view won't function as intended.

If all operations are successful (check the console for any warnings or errors), the new folder will appear in the tree view component. If any child components were found, they will appear under the folder as well.

During the NativeConstruct event, we iterate over all root-level items and execute the AddItem function on the UTreeView component. This populates Unreal Engine's internal data structure and additionally triggers the NativeOnListItemObjectSet function of the IUserObjectListEntry interface.

The importance of NativeOnListItemObjectSet will be discussed further below.

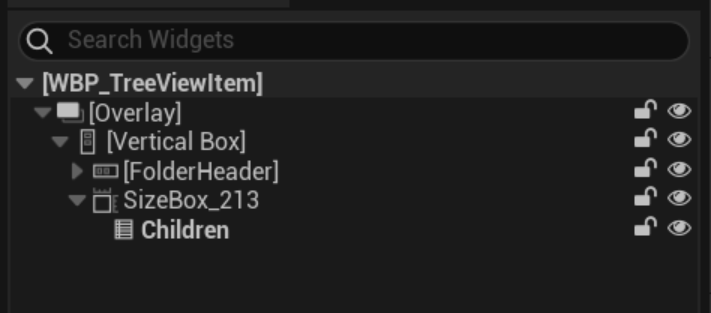

To specify the UUserWidgetBluerpint that is going to be displayed as an itme of the tree view we have configured the ListEntires of the TreeViewComponet to be WBP_TreeViewItem

Tree view entry widget

Associated classes CPP_TreeViewEntry, CPP_TreeViewEntryWidget,WBP_TreeViewEntryWidget

To style the folder entries in the tree view, we created a new class called CPP_TreeViewEntryWidget. This class inherits from UUserWidget and implements the IUserObjectListEntry interface. Additionally, we created a Blueprint class based on CPP_TreeViewEntryWidget to customize the appearance of the entries.

Within CPP_TreeViewEntryWidget, you’ll find bindings to components that are populated with data defined earlier. For instance, consider the folder label text. How does Unreal Engine know what text to display there? Suppose we are adding a folder named "Muscles" — how do we assign this label to the text field?

To accomplish this, we implement the IUserObjectListEntry interface, which includes an event triggered each time AddItem is called. This event receives item data as a UObject parameter, which we can then cast to the appropriate type, in this case, CPP_TreeViewEntry. By casting the data, we gain access to the child properties previously documented.

Since we’ve set up bindings to the text box, we can easily control the text that displays. In practice, this setup is straightforward and works as follows:

// UCPP_TreeViewEntry.cpp

void UCPP_TreeViewEntryWidget::NativeOnListItemObjectSet(UObject* ListItemObject)

{

IUserObjectListEntry::NativeOnListItemObjectSet(ListItemObject);

auto TreeViewEntryData = Cast<UCPP_TreeViewEntry>(ListItemObject);

FolderName->SetText(FText::FromString(TreeViewEntryData->GetFolderName()));

// explained later

for (auto &Child : TreeViewEntryData->GetChildren())

{

Children->AddItem(Child);

}

}

We were not able to figure out how to use tree view to its full extend but you can. This means that to display children of the CPP_TreeViewEntry we have used another build in wiget called ListView this widget works similuarly to the TreeView in a sense that it can display N componentes that have the same styling and that we can choose styling that we want thanks to the UMG

What this means in practise is that the parent a.k.a (UCPP_TreeViewEntryWidget) holds a bindable pointer to the ListView which we can populate with children passed to it during creation process

Tree view child entry widget

Associated Classes: CPP_TreeViewEntryChild, CPP_TreeViewEntryChildWidget, WBP_TreeViewEntryChildWidget, MeshSelector

As mentioned earlier, each TreeView entry contains a list view, representing the skeletal meshes that can be interacted with. To populate this list view, we created the CPP_TreeViewEntryChild class, which manages both the data and visual appearance of items within the ListView.

This process follows the same approach used for tree view items. The only difference is that we now iterate through the Children field of the CPP_TreeViewEntry class and execute AddItem on the bound pointer of the ListView.

void UCPP_TreeViewChildEntryWidget::NativeOnListItemObjectSet(UObject* ListItemObject)

{

IUserObjectListEntry::NativeOnListItemObjectSet(ListItemObject);

if(ListItemObject)

{

// cast from UObject to *CPP_TreeViewEntryChild to get the right data

auto TreeViewChildEntry = Cast<UCPP_TreeViewEntryChild>(ListItemObject);

ActorName->SetText(FText::FromString(TreeViewChildEntry->GetName()));

ReferencingActor = TreeViewChildEntry->GetActor();

ReferencingComponent = TreeViewChildEntry->GetComponent();

}

}

As seen in the implementation, both the referencing actor and the specific component are stored, allowing efficient access to both the Blueprint that contains the picker and merged meshes, as well as the pointer to the individual merged body part. This design is more efficient than repeatedly retrieving all children and helps reduce memory bandwidth usage.

The logic for hiding child elements is straightforward. A key detail is that when we hide the skeletal mesh, we also disable the collision on all its child components (picker meshes) to ensure they are truly perceived as hidden. This is implemented inside the HideAll and ShowAll functions in C++ and they are called from the Blueprint for better organizations and maintainability.

Highlighting is managed through the MeshSelector class, which we retrieve as a pointer using the AnatomyUtils helper namespace. Additionally, we pass the component (the skeletal mesh) referenced by the child element as a parameter to the highlight function.

void UCPP_TreeViewChildEntryWidget::Highlight()

{

AnatomyUtils::GetMeshSelector(GetWorld())->HighlightComponent(ReferencingComponent);

}